Africa And The Indian Sub continent: Islamic Colonization

In this article, I am going to talk about the spread of Islam at one level, the first one, among the three level. My main aim is to show that we can use the same framework to understand the spread of Islam in the Indian Sub- continent, although we have to be cautious about saying that the spread of Islam in the Indian sub- continent is an exact mimicry of the one in Africa. In order to understand the spread of Islam in Africa, we have to understand the concept of Jihad. According to Dr. Azuma, There are many versions of “Jihad” and there are no agreements on Jihad. “Jihad” is an Arabic verbal noun derived from the verb “Jahada”, which means “strain”, “exertion”, “endeavor” on behalf or for the sake of something. Jihad is translated by E.W. Lane as “the using or exerting one’s utmost power, efforts, endeavors, or ability in contending with an object of disapprobation… namely a visible enemy, the devil, and one’s self (Azuma, p, 138). Lane goes to the point out that jihad came to be used by Muslims to signify fighting or waging war against “unbelievers and the like” as a religious duty. “

• Jihad mainly evolved out of intra Muslim conflicts. For the purpose of this essay we have to make a distinction among the following three jihads:

• Jihad bi al-nafs: is the greater against one’s sinful inclinations.

• Jihad bi al-sayf: Jihad of the sword

• Jihad al-qawl: Preaching of the tongue

Hill points out, the spread of Islam in Africa is a complex process consisting of three layers (Hill, 2009). Hill calls these three stages, containment, mixing, and reform. Here we are going to talk of “containment” or “enclavement” and in subsequent essays about the other two.In order to understand this complex process, we first have to learn about how land was viewed in the traditional African indigenous community.

In order to understand the land question in indigenous Africa, we have to note two important things:

- Only the community not individual had land rights.

- Rights in occupancy depended upon residence within the community

- The community represented by the chief, exercised the control, occupation and the use of land.

- Land could not be bought and sold in the market, but could only be transferred through inheritance, gift or temporary bias (Azumah, p, 56)

The chief of a village had rights to sell the produce of the land and the community put trust in the chief. The chief always came from a royal lineage, i.e., first settler. He is not just a political head but also the preserver of the ancestral culture. He carries the culture of the tribe in his vein. In a village everybody is kin. There is blood relation or relation established via marriage. This has far-reaching implications. For example, say in the Zulu tribe, the term “zulu” stands for both his ethnic as well as his religious or faith identity. According to Azumah, the African understanding of religion is non institutionalized and non codified systems of beliefs and practices. In other words, one can talk of “religiosity” but not religion. The African way of life is being immersed in religion. The only definition of religion is not in the pages of books but in the hearts and minds of people (Azumah, p, 48). The following will make the point clear:

“African language have no equivalent for the western word religion or the indeed “ritual”. An old traditionalist on being asked his religion would reply, “I am Zulu” (Azumah, p, 48). So, belonging to a tribe is the same as having a religion. Here we see a similarity with Hindus. Being Hindu is a praxis, not codified in law and being a Hindu is the same as belonging to a nation, race, ethnicity. The modern concept of a nation does not go well with the identity of being a “Hindu”.

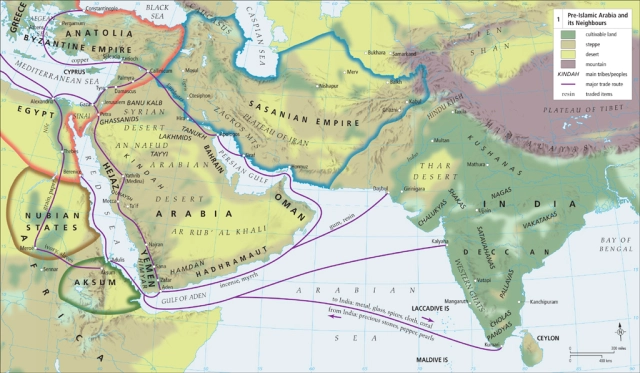

Having understood the African notion of land systems and ethnicity, let us try to understand next the concept of “enclavement”. Africa had age old trade with people from the Middle East and the Southern Mediterranean. Nonetheless, they did not reside and try to spread their culture or faith. The Muslim traders did long distance trade and they came into Africa and brought in long distance trades. They often resided in the indigenous kingdoms. There was a tradition of “enclavement” where the Muslim traders would be given a separate place within the kingdom to reside, pray, follow their own custom, and so on. Some of these traders also acted as spiritual healers and other healers also arrived with them or a little after them. Since they were non kin groups and had no blood relations, they were not allowed to mix with the indigenous population but were give right to do business and protection, and were treated almost like kins. They lived in the “enclavement” and got protection from banditry, safe passage through hostile land and patronage for the promotion of their business. In the indigenous religion and culture, there is a implicit openness and inclusiveness that one could stay in the community, although separately from the kin groups, but it permitted the appropriation and exchanges of ideas and rituals at the communal level without changing one’s religion (Azumah, p, 50). This is an echo of the Indian “Vasudev Kutumbakam” philosophy of India. These traders were called “Dyula” and they brought with them several things, which the ordinary people of the indigenous community and next the Royalty also used. The Pirs brought in amulets and talismans, provided healing arts, prayers sought to win war coats and hats (produced stitched with leather saphies or silvered amulets with Quranic verses) to paralyze the enemy’s hand, shiver his weapons and divert his course. These were used both by the ordinary people as well as the Royalty.

The most important thing, however, that they bought with them was writing and literacy. This was how Muslims exerted their sphere of influence in the Royal Court. According to Azumah, “… the literary expertise of the Muslim divines became invested with a supernatural power, particularly where writing is primarily a religious activity. The special technological enterprise, i.e., writing: the alphabet, pens, ink, paper, earned Muslim religious men high esteem and reverence in the wider society. The traders, on the other hand, were welcomes wand held in high esteem because of their wares such as salt, cloth, etc. In addition to this, traditional African respect and homage to religious objects and personalities as sacred and extended to Muslims and their lives were regarded in most traditional societies as inviolable.” (Azumah, p, 43).

Now, back to the Sub continent. Here, though there are some similarities, there is also difference. In the sub continent, the Muslim traders came first, then also the Muslim religious Divines, who spread the word of the Islam and also sold important articles. Nonetheless, there is a difference, first, there was already a system of healing, the art of medicine or Ayurveda, and a system of writing in the sub continent. So, the use of these two were less important, although probably, people in the Sub continent were using some of the healing brought in my the Pirs and Sufis.

In my next blogs I will write about the process of (a) conversion in Africa and the Sub continent (b) why the Jihad al-Qwal di not work well and how Jihad bil’l sayf had to be introduced in Africa and the Sub continent.

References:

Azumah, J. A. (2018). The Legacy of Arab-Islam In Africa. Oneworld.

Hill, M. (2009). The Spread of Islam in West Africa: Containment, Mixing, and Reform.